Acute or sudden vision loss is due to one of the following causes:

- Opacification of normally transparent structures anterior to retina

- Retinal abnormalities

- Abnormalities of optic nerve and visual pathway

Systematic history and ocular examination is necessary.

Step 1: Unilateral or Bilateral Sudden vision loss ?

- Monocular loss of vision: lesion anterior to optic chiasma

- Binocular loss of vision: lesion posterior to optic chiasma

Step 2: Painful or Painless Sudden Vision loss?

- Constant eye pain: Corneal lesion, Anterior chamber inflammation or Increased IOP

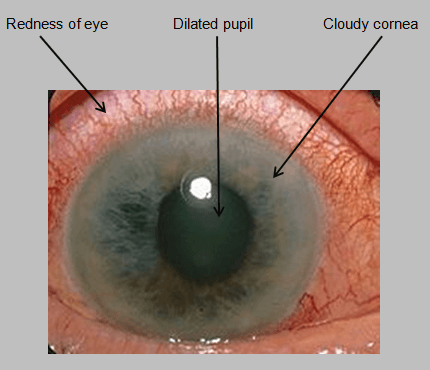

Features of Acute congestive glaucoma:

Features of Acute congestive glaucoma:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Colored halos around lights

- Unreactive and fixed mid-dilated pupils

- Hyperemic conjunctiva

- Corneal edema demonstrated by a dulled reflection of light from the corneal surface

- Features of Corneal lesion:

- Ask for history of Contact lens wear

- Photophobia

- Perform fluorescein staining of corneal defect

- Features of Endophthalmitis:

- History of recent intraocular surgery or trauma

- Floaters

- Conjunctival injection

- Decreased red reflex

- Hypopyon

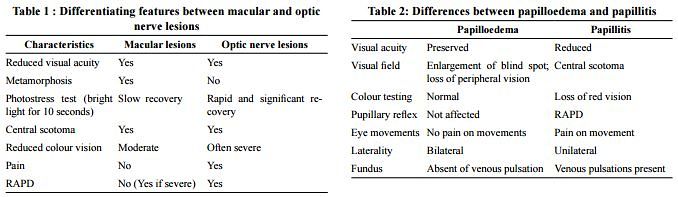

- Eye pain with movement: Optic neuritis

- Additional features: RAPD, central visual field defect, red desaturation (abnormal color vision)

Step 3: If the condition is painless sudden vision loss:

A) Onset and duration ?

- Transient visual loss: Vascular cause, Papilledema or Migraine

- Headache: Giant cell Arteritis or Migraine

- Migraine: Young patients; Scintillating scotomata, fortification spectra, or complete loss of vision lasting usually lasting less than an hour; Unilateral headache and aura

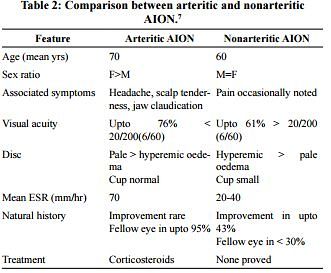

- Giant cell arteritis: Elderly patients; jaw claudication, scalp tenderness, headache, malaise, anorexia, and proximal joint or muscle aches, pulseless or thickened temporal artery

- Features of raised ICP: Papilledema

- Carotid bruit, Evidence of emboli, Atrial fibrillation: Amaurosis fugax

- Recurrent episodes, Cerebellar signs, Hemiparesis, Hemisensory loss: Vertebro-basilar insufficiency

- Headache: Giant cell Arteritis or Migraine

- Persistent visual loss: Abnormality of cornea, vitreous, fundus, cortex or a functional cause

B) Floaters?

- Retinal detachment: Photopsias (brief monocular flashes of light), Curtain or shadow moving in the field of vision

- Others: Intermediate and Posterior uveitis

C) Relative Afferent Pupillary Defect (RAPD) on Swinging light test ?

- Altitudinal visual field defect: Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (AION)

- Features of retinal detachment: Severe retinal detachment

- “Tobacco dust” in vitreous on slit-lamp examination: Rhegamtogenous retinal detachment

- Evidence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypercoagulable state: Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) or Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO)

Step 4: Findings in fundoscopy in sudden vision loss ?

A) Difficulty seeing red reflex: Opacification of transparent structures ahead of retina

B) No difficulty seeing red reflex:

- Papilledema: bilateral optic disc swelling, loss of spontaneous venous pulsation (SVP), peripapillary hemorrhages

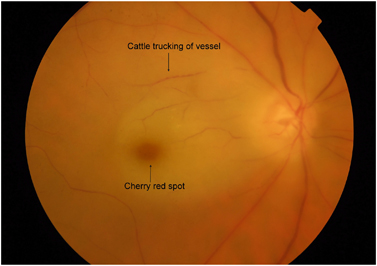

- CRAO: attenuated arterioles, box carring of retina vessels, pale fundus, cherry-red spot, Hollenhorst plaque (refractile object at the site of arterial occlusion)

- CRVO: dilated tortuous veins, hemorrhages in all four quadrants, ± cotton wool spots, retinal edema

- Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: corrugated elevated retina with (multiple) break(s)

- Exudative retinal detachment: convex elevated retina with shifting fluid, no break; tractional: concave elevated retina with tractional membranes

- Intermediate uveitis: macular edema, optic nerve edema

- Posterior uveitis: retinal/choroidal infiltrates, macular edema, vascular sheathing or occlusion, hemorrhages.

- Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: pale edematous disc ± flameshaped hemorrhages

- Choroidal neovascular membrane (Wet ARMD): drusen, subretinal membrane ± hemorrhage, exudate

Step 5: If pupillary light reflexes are normal – Check optokinetic nystagmus

If an optokinetic drum is unavailable, a mirror can be held near the patient’s eye and slowly moved. If the patient can see, the eyes usually track movement of the mirror.

- Absent: Occipital lesions

- Present: Functional visual loss

INVESTIGATIONS FOR SUDDEN VISION LOSS:

Based on the disorder suspected from the history and clinical examination:

- ESR, CRP, Platelets: whenever Giant cell arteritis needs to be excluded as the possible cause (All increased in GCA)

- If suggestive, temporal artery biopsy must be done within 7 days of starting steroids to confirm the diagnosis.

- MRI/CT: to rule out central lesions and demylenating lesions as a cause of optic neuritis

- Culture of anterior chamber and vitreous fluids: Endophthalmitis

- ECG, Carotid ultrasonography: Cardiovascular cause

- USG-B scan: Retinal detachment

- Gonioscopy: Acute congestive glaucoma (ACG)

MANAGEMENT OF CAUSES OF SUDDEN VISION LOSS:

1. Acute Congestive Glaucoma:

a. Immediate:

- Systemic: acetazolamide 500 mg IV stat, then 250 mg PO 4x/day

- Ipsilateral eye:

- B-blocker e.g., timolol 0.5% stat, then 2/day

- Sympathomimetic e.g., apraclonidine 1% stat

- Steroid e.g., prednisolone 1% stat, then q30–60 min

- Pilocarpine 2% Once IOP <50 mmHg; e.g., twice in first hour then 4x/day

- Consider corneal indentation with a 4-mirror goniolens, which may help relieve pupillary block.

- Laying the patient supine may allow the lens to fall back away from the iris.

- Analgesics and anti-emetics may be necessary.

- Promptly assess and treat contralateral eye with laser PI (LPI).

b. Intermediate:

- Check IOP hourly until there is adequate control.

- If IOP is not improving, consider systemic hyperosmotics (e.g., glycerol PO 1 g/kg of 50% solution in lemon juice or mannitol 20% solution IV 1–1.5 g/kg).

- If IOP is still not improving, consider acute LPI (can use topical glycerine to temporarily reduce the corneal edema).

- If IOP is still not improving, review the diagnosis (e.g., could this be aqueous misdirection syndrome or neovascular glaucoma?), consider repeating LPI, or proceeding to surgical PI or even emergency trabeculectomy.

c. Definitive: Bilateral laser (e.g., Nd-YAG) or surgical PI

2. Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (AION):

a. Immediate:

- IV Steroid treatment (e.g., 1 g methylprednisolone IV 1x/day for 1–3 days)

- Followed by oral prednisolone 1–2 mg/kg 1x/day)

- Aspirin may have additional benefit.

b. Maintenance: Steroids may be titrated according to symptoms and inflammatory markers (CRP responds more quickly than ESR).

3. CRAO:

- Medical emergency and the visual loss is irreversible

- Attempt to reduce IOP in affected eye:

- 500 mg IV acetazolamide, ocular massage ±

- AC paracentesis ocular

- Selective ophthalmic artery catheterization with thrombolysis if available

- Protect other eye, e.g., treat underlying GCA with systemic steroids immediately

- Panretinal photocoagulation with argon, krypton, diode, etc. laser prevents neovascularisation

4. CRVO:

- Reduce IOP: if elevated (in either eye)

- Panretinal photocoagulation for neovascularization or high risk.

- Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide or intravitreal dexamethasone implant for treatment of CME.

- Intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab for treatment of CME and neovascularization.

- Pars plana vitrectomy and endolaser for vitreous hemorrhage secondary to neovascularization.

- Treat underlying medical conditions

5. Optic neuritis:

- IV steroid treatment may be offered to those with poor vision in the other eye or with severe pain.

- In those at high risk (>2 plaques on MRI), interferon B1a appears to reduce or at least delay both the clinical diagnosis of MS

7. Giant cell arteritis:

- Immediate high dose steroids (e.g. oral prednisolone 60 mg OD) without delay. The aim is to prevent contralateral loss of vision.

- Urgent rheumatology referral is warranted.

- Steroids may be required for up to two years with doses based on monitoring of symptoms and ESR.