Ketosis and Ketonuria

Ketosis and Ketonuria may occur whenever increased amounts of fat are metabolized, carbohydrate intake is restricted, or the diet rich in fats (either “hidden” or obvious). This state can occur in the following situations:

a. Metabolic conditions:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Renal glycosuria

- Glycogen storage disease (von Gierke’s disease)

b. Dietary conditions:

- Starvation, fasting

- High-fat diets

- Prolonged vomiting, diarrhea

- Anorexia

- Low-carbohydrate diet

- Eclampsia

c. Increased metabolic states caused by:

- Hyperthyroidism

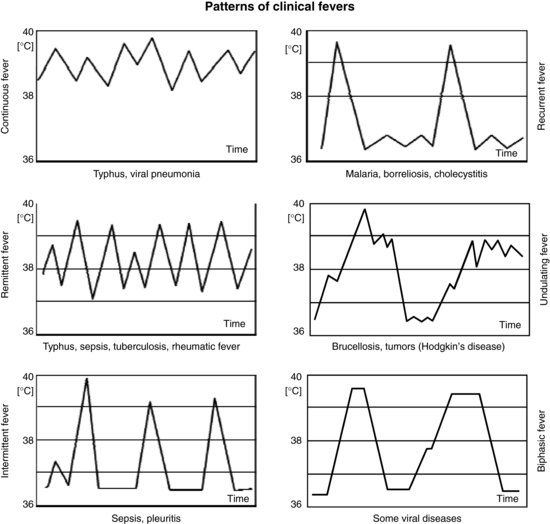

- Fever

- Pregnancy or lactation

In non-diabetic persons, ketonuria occurs frequently during acute illness, severe stress, or sternous exercise. Approximately 15% hospitalized patients have ketones in their urine even though they do not have diabetes. Children are particularly prone to developing ketonuria and ketosis.

Ketonuria signals a need for caution, rather than crisis intervention, in either a diabetic or non-diabetic patient. However, this condition should not be taken lightly.

- In the diabetic patients, ketone bodies in the urine suggest that the diabetes is not adequately controlled and that adjustments of either the medication or diet should be made promptly.

- In the non-diabetic patients, ketone bodies indicate a reduced carbohydrate metabolism and excessive fat metabolism.

- Positive ketone urines in a children younger than 2 years of age is a critical alert.

Difference between Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Diabetic ketosis or ketonuria

The criteria for diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) include:

- Blood glucose >250 mg/dl

- Ketonemia or ketonuria (plasma beta0hydroxybutyrate >3 mmol/l or urine ketones ≥3+)

- pH <7.3 or serum bicarbonate <15 mEq/L

In a patient with diabetes, presence of hyperglycemia and ketosis in the absence of acidosis is consistent with a diagnosis of diabetic ketosis.

The presence of ketosis and acidosis in a diabetic patient with blood glucose <250 mg/dl is termed euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis.

Diabetic Ketosis and Ketonuria

In some patients with diabetes (for example, those with type 1 diabetes of 1 year or more duration), there is essentially no insulin production. In the absence of insulin secretion with pronounced secondary hyperglucagonemia, ketone body production accelerates. Ketones are not reabsorbed by the kidney tubules. Therefore, ketones appear in the urine (ketonuria) as soon as the rate of ketone body production exceeds the rate of ketone body consumption. Ketonuria is therefore a marker of poorly controlled diabetes.

There are no real symptoms of ketosis, except sometimes a fruity smell to the breath. Ketones, metabolites of fat, are the body’s clue to insulin insufficiency. Because, insulin is a very potent antilipolytic hormone, it takes a greater degree of insulin deficiency for ketosis to occur than for hyperglycemia to occur. This ususally means that overeating can cause a person to become very hyperglycemic, with blood glucose levels in the many hundreds, but overeating itself will not cause ketosis. Ketones are more likely to be formed in response to not taking insulin, not taking enough insulin, or having a significant illness. During very low carbohydrate intake, the regulated and controlled production of ketone bodies causes a harmless physiological state known as dietary ketosis. In ketosis, the blood pH remains buffered within normal limits.

Management of Diabetic Ketosis without Ketoacidosis

It is vital for treating physician or nurses to to appreciate the difference between ketosis and DKA. This is a particular issue in the anorexic or dieting type II diabetic who shows moderate ketonuria: do you rush in with a DKA regimen, or can you reassure the patient? This depends on the clinical picture. In general, ketonuria is much more likely to indicate impending ketoacidosis in the thin type I diabetic than in the obese patient whose diabetes is controlled with oral hypoglycemics. Moreover, the patient with ketoacidosis is likely to have warning symptoms: thirst, hyperventilation and nausea. A diabetic patient with moderate ketonuria may look “too well” for DKA; check for acidosis. A simple venous blood sample for plasma bicarbonate will reveal if there is cause for concern; if the bicarbonate is low (less than 15 mmol/l) there is acidosis, if it is normal, then both physician and patient can be reassured.

Increasingly, the patient with type 1 diabetes are given ‘sick day rules‘ for how to manage this when appropriate out of hospital. This relies on the patient being fully conscious, not vomiting and being willing and able to drink fluids and follow instructions, including regular and repeated monitoring of blood glucose and ketone levels. In general, insulin doses are increased with additional injections of soluble insulin (10-20% of total daily insulin dose every 2 hours). The rules include ‘bail out’ instructions on seeking admission if ketone and glucose levels are not resolving and/or patient starts to vomit or fail to improve clinically.

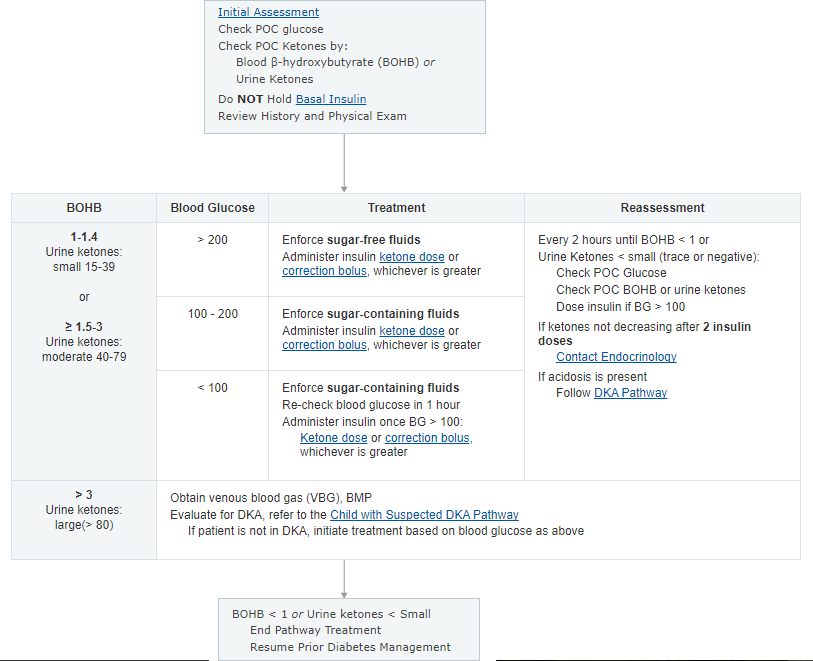

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) has developed a pathway for management of Diabetic Ketosis without acidosis.

Insulin Dosing

Ketone Dose, Correction Factor, and Correction Bolus Calculation

Administer ketone dose OR correction bolus, whichever is greater, but not both.

| Calculation | Description | Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Ketone Dose |

|

|

| Correction Factor |

|

|

| Correction Bolus |

|

|

Example

- Correction Factor Calculations

- Patient has a total daily insulin dose of 35 units.

- Correction factor = 1800 / 35 = 50

- 1 unit of insulin will lower blood glucose by 50 points (1:50)

- Correction Bolus Calculation

- Patient blood glucose is 300 mg/dL, TDD insulin dose of 35 units and correction factor = 50

- Target blood glucose 100 mg/dL

- Correction bolus = (300-100) / 50 = 4

- Patient should be administered 4 units of insulin

- Ketone Dose Calculation

- Patient with blood glucose of 300 and BOHB > 1

- 10% of TDD yields Ketone dose = 3.5 units

- Administering the Dose

- Give whichever dose is greater

- Since the correction factor is greater, this patient should receive the correction bolus only

References:

1. Diabetes Mellitus: Pathophysiology, Etiologies, Complications, Management, and Laboratory Evaluation By William E. Winter, Maria Rita Signorino

2. Clinical Pharmacology By Morris J. Brown, Pankaj Sharma, Peter N. Bennett

3. A Manual of Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests By Frances Talaska Fischbach, Marshall Barnett Dunning

4. Clinical Rounds in Endocrinology: Volume I – Adult Endocrinology By Anil Bhansali, Yashpal Gogate

5. Clinical Management of the Child and Teenager with Diabetes By Leslie Plotnick, Randi Henderson

6. Acute Medical Emergencies: A Nursing Guide By Richard Harrison (M.D.), Lynda Daly

7. Diabetic Ketosis without acidosis, Evaluation/Treatment, Clinical Pathway – Inpatient

thank you.