“No disease of the human body, belonging to the province of the surgeon, requires in its treatment a greater combination of accurate anatomic knowledge, with surgical skill, than hernia and all its varieties.”

– Sir Astley Cooper

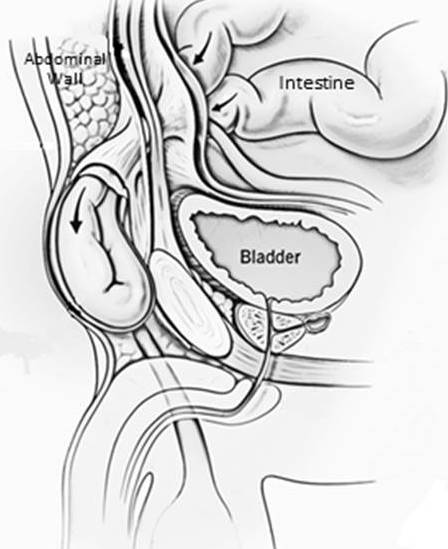

‘Hernia’, a word derived from Latin for ‘Rupture’, defined as the unusual protrusion of the contents of any cavity through a defect in its walls. Incidence of a person developing hernia in his lifetime is about 27% in males (3% in females). Among all hernias, abdominal hernia is one of the common situations presenting to the OPD and also to be operated. Hernia is a long known condition in humans, but the first documented evidence was by the Egyptians in 1550 B.C.

In the mid-19th century was the first time a surgical approach was considered as a treatment for Hernia, until then it was a non-surgical method of therapy such as diet modifications, enema and trusses. Usually Castration was done followed by closing the wound, which led to high rates of recurrence and as they were aseptic methods then, mortality was also high.

Gradually as the modern surgical era began, three rules were put forward for the surgical management:

- Asepsis

- High Ligation of Hernia Sac

- Narrowing of the Internal Inguinal Ring

Later few others were added so as to bring down the recurrence rates and complications, reconstructing the posterior inguinal wall and tensionless repair were the fourth and fifth rules.

Many modifications in the methods of surgery were made since then, from using synthetic materials for reinforcement to using a mesh to laparoscopic repair.

Abdominal Hernia

Abdomen is a complex division of the body consisting number of organs, it is enclosed by bones, layers of muscles and fascia together known as the Abdominal Wall. The wall extends from the costal margin above to the pelvic ring below and vertebral column posteriorly.

Hernia in the abdomen can occur in various regions:

Inguinal, Femoral, Umbilical, Incisional, Lumbar, Epigastric, Obturator

Anatomy and Physiology of Anterior Abdominal Wall

Structures of the abdominal wall are derived from the mesoderm originating from the paravertebral region and reach the anterior midline forming the Rectus Abdominis Muscle on either side. It is covered by an aponeurosis which fuses in the midline as Linea Alba. Rectus Abdominis is a longitudinal, strong muscle extending from the ribs to pelvic bone.

Lateral to the rectus muscle are three layers of muscles – External Oblique, Internal Oblique and Transversus Abdominis. These muscles are arranged obliquely to each other.

Under these are Fascia Transversalis, Extra-Peritoneal Fascia and Peritoneum.

The muscles of the abdomen apart from keeping the organs in place also tend to increase the intra-abdominal pressure. This aids to upward displacement of Diaphragm leading to Expiration. The increased pressure also helps in micturition, defecation and parturition provided Diaphragm is contracted (Valsalva Procedure).

The muscles also involve in rotation and bending of the trunk.

Anatomy of Groin, Inguinal Ligament and Canal

Inguinal (or Poupart’s) Ligament is the inferior edge of the External Oblique Aponeurosis, with a posterior turn creating a shelf which extends from the Anterior Superior Iliac Spine to Pubic Tubercle. An extension of this ligament is the Lacunar Ligament which is reflected backward as Pectineal (or Cooper’s) Ligament and inserts into the Pectineal Line. The Lacunar Ligament forms the medial boundary of the Femoral Canal.

In the External Oblique Aponeurosis is an Ovoid Opening, the Superficial Inguinal Ring. It is present Superior and Lateral to Pubic Tubercle.

The Internal Oblique laterally forms the Cremasteric Muscle which surrounds the Spermatic Chord (Round Ligament in women) and continues in the Inguinal Canal. Medially it merges with the Transversus Abdominis forming the Conjoint tendon, inserting into the Pubic Tubercle.

The Transversus Abdominis arches over the Deep Inguinal Ring and then merges with Internal Oblique. The arch is known as the Aponeurotic Arch.

Deep Inguinal Ring is a defect in the Fascia Transversalis. Fascia Transversalis is a aponeurotic membrane covering the internal surface of Transvesus Abdominis. The Ring is located slightly above the Mid-Point of Inguinal Ligament.

Ilio-Pubic Tract is the region behind the Inguinal Ligament formed from Transversus Abdominis and Fascia Transversalis, an important area to be localized during repair, where in staples should not be placed lateral to the deep inguinal ring owing to the presence of Lumbar Plexus.

Inguinal Canal is a 4 cm long tube like structure directed infero-medially and anteriorly between Deep and Superficial Inguinal Rings. The main contents are Spermatic Cord (in men) and Round Ligament (in women) and Ilio-Inguinal Nerve.

Spermatic Cord – A cord like structure containing nerves, vessels and other structures that run to and from the testis.

Vasculature of importance in and around the groin constitutes, the Inferior Epigastric Vessels which differentiate between Direct Inguinal Hernia (medial swelling) and Indirect Inguinal Hernia (lateral swelling).

Nerves of importance in and around the groin constitute:

a) Ilio – Hypogastric Nerve, an anterior branch of the Lumbar Plexus which gives a lateral branch providing sensory innervation to posterolateral gluteal region and the anterior branch provides sensory innervation to Skin of Groin, Base of Penis and Upper Scrotum (Mons Pubis and Labia Majora in women).

b) Ilio – Inguinal Nerve, also an anterior branch of Lumbar Plexus, receives few fibers from Ilio – Hypogastric Nerve (anterior branch) and supplies Skin of Groin, Base of Penis, Upper Scrotum (Mons Pubis and Labia Majora in women) and Medial Thigh.

c) Genital Branch of Genito – Femoral Nerve, a component of the Genito – Femoral Nerve which is a derivative of L1 – L2 roots, provides sensory innervation to anterior part of the scrotum (mons pubis and labia majora in women). It also provides motor innervation to the Cremasteric Muscle facilitating the Cremasteric Reflex.

Why does Hernia occur?

Although the abdominal cavity is enclosed by layers of muscles and fascia, but the connection to adjacent regions through natural openings lead to protrusion of the contents.

- Weakness in a region of the abdominal wall also may lead to various hernias.

- On increased intra-abdominal pressure and inability of the wall to contain the contents, they may herniate through the openings / weakness’s, in conditions such as Chronic Cough, Obesity, Weight Lifting, Straining on Micturition & Defecation, Ascites and Abdominal / Thoracic Aneurysm. Few familial connective tissue disorders are also probable causes leading to hernia such as, Ehler-Danlos Syndrome, Marfan’s Syndrome, and Metalloproteinase Deficiencies due to the lax muscles and fascia. Some miscellaneous causes include ageing, pregnancy, neurological and muscular disorders.

- Evolution from quadrupeds to bipeds, leading to the erect posture compromises the strength of the abdominal wall especially at the groin making it vulnerable to develop inguinal hernia.

- Developmental defects such as Patent Processus Vaginalis (canal of Nuck in women) and incomplete obliteration of umbilicus may lead to the respective hernias.

- Weakness in the abdominal wall due to a stab / incision, may lead to Incisional Hernia as the healed wounded tissue is not as strong as an unwounded tissue.

How is a Hernia described?

A swelling seen on the surface of a cavity containing its contents through a natural opening or a weakness created is called a Hernia.

What is the fate of Hernia?

The consequences of hernia depend upon the character of the opening in the wall of the cavity and the contents in the sac. A small opening (i.e. mouth of the sac) with rigid wall which prevents the free movement of the contents in and out of the sac will succumb to complications.

A long standing hernia may lead to formation of adhesions, which leads to restricted movement of the contents hence the complications.

Further, on neglecting the situation serous fluid is seen oozing out into the sac, which is a medium of growth of bacteria (Trans-serosal Migration). Eventually the wall of the content becomes weak and friable leading to perforation followed by peritonitis.

Summary

- Hernia is a well known condition in humans since ancient times, which often lead to mortalities owing to the lack of knowledge regarding the anatomy and the mode of treatment. As time passed by, light was shown onto anatomy many surgeons put efforts on treating the condition.

- Hernia is classically defined as “Protrusion of the contents of a cavity through its walls”.

- Abdominal Hernias are much more common than other types of hernia among which Inguinal Hernia are the most common.

- This is due to few natural openings in the abdomen which in increasing the intra-abdominal pressure the contents would force out as a swelling. It is also due to the compromise in the strength of the abdominal wall in course of evolution into an erect posture.

- Hernia if neglected may lead to complications and even cause fatality on a later date.

References

- Katedra Chirurgii Ogólnej CM UJ, Kraków, Folia Med Cracov. 2008;49(1-2):57-74.

- Netter’s Clinical Anatomy, 3rd Edition.

- Snell’s Clinical Anatomy, 10th Edition.

- Bailey & Love’s Short Practice of Surgery, 27th Edition.

- Greenfield’s Surgery Scientific Principles and Practices, 6th Edition.

- Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 20th Edition.

Graduated from one of the famous institutions in Telangana, Kamineni Institute of Medical Sciences. He has always been fond of writing articles in Medicine. Since the undergraduate years was interested in making creative Presentations and taking seminars.